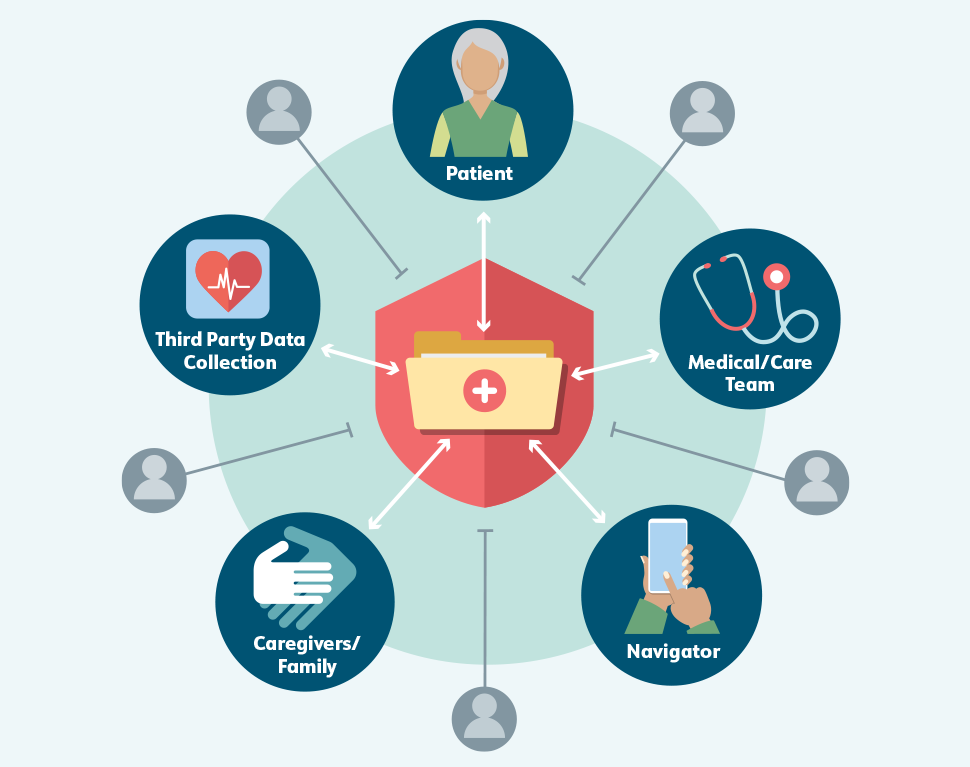

The cancer journey creates vast quantities of patient health data, including test results, referrals, prescriptions, visit summaries, and communications between patients and caregivers and their care teams. Effective cancer care delivery depends on the timely exchange of these data. At the same time, sensitive health information must be kept both private and secure. In an ideal world, data sharing would protect patient information without impeding its access and use by appropriate parties, including patients themselves (Figure 5).

Current circumstances are far from ideal. Patients, caregivers, navigators, and clinicians all experience significant obstacles in accessing and sharing health-related data. Even within a health system, technological or logistical barriers can prevent team members from exchanging vital patient information. (1,2) The challenges are often even greater when trying to share between healthcare organizations, with patients directly, or with third parties. Yet, outside the healthcare setting, individuals’ health-related data can be shared too freely, without appropriate protections (see Recommendation 4.2).

To create a seamless workflow for cancer patient navigation, patients and care teams—including navigators—need access to different types of data from different sources. These data are currently collected through and stored in many discrete streams, each with its own format and exclusive audience; in some settings, for example, community health workers may not be able to access their patients’ electronic health records (EHRs), while clinicians may not be able to view patient navigators’ notes or referrals to resources.

Figure 5. Balancing Data Sharing with Privacy and Security

Recommendation 4.1: Improve and incentivize interoperability to enable portability of patient data across health IT platforms and systems in order to improve navigation.

Interoperability is the capacity of health IT systems and software applications to communicate, exchange data, and use the information that has been exchanged without special effort on the part of the user. A recent survey found that more than half of people who had recently been diagnosed with cancer had multiple patient portals or EHRs; patients with cancer also had a higher average number of EHRs and patient portals compared with people who had never been diagnosed with cancer. (3) The need for interoperability in health information technology has been a topic of discussion in the cancer community for some time and was even identified as an urgent priority in the 2016 President’s Cancer Panel report, Improving Cancer-Related Outcomes with Connected Health. (1)

Since the publication of that report, the federal government has made significant progress toward this aim. The Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy/Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ASTP/ONC) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) leads and coordinates interoperability efforts, including standards development and health information technology certification, as well as policy and programmatic initiatives in partnership with the healthcare industry. (4) ASTP/ONC is charged with providing technical assistance across the Department under the HHS Health IT Alignment Policy, which requires HHS-funded initiatives to use aligned standards for health IT with the goal of advancing interoperability between and among all parts of the healthcare and public health community. (5) ASTP/ONC also defines functional requirements for the voluntary certification of health information technology. This certification has great influence; as of 2017, more than 96% of nonfederal acute care hospitals were using certified health information technology. (6) In January 2024, ASTP/ONC finalized its Health Data, Technology, and Interoperability: Certification Program Updates, Algorithm Transparency, and Information Sharing (HTI-1) rule. The final rule advances core data standards for interoperability and requires developers of certified health information technology to report on metrics related to interoperability. (7,8)

In addition, ASTP/ONC oversees the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA), which was described in the 21st Century Cures Act. The goals of TEFCA are to establish a universal governance, policy, and technical floor for nationwide interoperability; simplify connectivity for the secure exchange of clinical information; and enable individuals to access their own health data. Version 2.0 of the Common Agreement was released by ASTP/ONC in April 2024. (9) The updated agreement defines baseline legal and technical requirements for secure information sharing nationwide and lays out a common set of principles to facilitate trust. (10) TEFCA aims to help address impediments to electronic information exchange, including for small and rural healthcare providers, many of whom still use mail or fax more frequently than electronic means to share data. (11)

Continued progress toward interoperability and the seamless and secure exchange of health data to support cancer patient navigation and care will depend not only on regulations and guidance but also on cultural shifts within individual institutions and across the healthcare industry. For many years, health systems have focused more on cost conservation and data security, a perspective that shapes their interpretation of laws and policies like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). (12) This orientation is understandable but can result in the unintended consequence of deprioritizing the most important aspect of healthcare: ensuring that patients get the care they need. The federal government can support these shifts by continuing to incentivize collaboration. The Panel acknowledges the many strides taken toward interoperability to date and encourages continued progress at the federal, industry, and health system levels. Future efforts should include targeted investments to support participation of small practices in health information exchanges.

Recommendation 4.2: Evaluate existing privacy and security regulations and laws and identify opportunities for a national legal framework to protect patients while fostering technological innovation to support patient navigation.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule, adopted in 2000, established the first national standards to protect individuals’ medical records and other individually identifiable health information. (13) The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act and the subsequent HHS rule amended HIPAA, created a breach notification rule, and incentivized the adoption of EHRs. (14,15) With these modifications, HIPAA rules apply to covered entities—including health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, and healthcare providers who transmit health information in electronic form*— as well as business associates of the covered entities. (16)

The technological landscape has changed significantly since HIPAA and HITECH were enacted. As of 2021, more than 350,000 mobile health (mHealth) apps were available for smartphones, tablets, and other devices. (17) More than half of U.S. adults report having used an mHealth app within the past 12 months (Figure 6). (18) Although these apps generate, store, and use individuals’ health data, in most cases they are not considered covered entities or business associates under HIPAA and therefore are not subject to HIPAA standards of privacy and security. (19,20) Standard modes of communication have also shifted. Many people prefer to communicate and receive information via social media and text messages, which are generally not considered to be secure.

Many organizations and individuals, including from the President’s Cancer Panel, (21) have raised concerns that HIPAA impedes biomedical research and healthcare and inadequately protects patient data. A 2009 report from the Institute of Medicine noted that different interpretations of HIPAA requirements across institutions created barriers to research and urged HHS to provide clearer guidance to address this. (22) Although the HHS Office for Civil Rights provides extensive information on HIPAA interpretation and compliance, (23) overly cautious interpretations of HIPAA and fear of lawsuits are still cited as barriers to data sharing. (24) Efforts to follow the letter of the law and avoid data breaches are commendable but result in considerable data access challenges for health systems, care teams, researchers, and patients and their families. These challenges will only grow as patients increasingly want to integrate their health information across healthcare organizations and platforms.

There have been efforts to protect the large and growing body of health data that falls outside the purview of HIPAA. Some states have enacted their own privacy rules to provide additional protections. These state-level laws are designed to help patients and can close gaps in information-sharing that could expose individuals’ information. Unfortunately, the resulting inconsistency across state lines creates significant compliance and cost challenges for health information technology developers and for institutions. (25)

The federal government also is working to address this gap from multiple perspectives. The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) Health Breach Notification Rule, which applies to mHealth apps and similar technologies, requires companies to notify consumers following breaches that may involve unauthorized disclosures of their health information. (19) Section 5 of the FTC Act prohibits unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce, including those related to the privacy and security of personal information in mHealth apps, while Section 12 prohibits false advertising. (19) The U.S. Food and Drug Administration enforces the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which, among other things, regulates the safety and effectiveness of medical devices, including some mHealth apps. (19) A 2019 report from the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics offered a new framework for the protection of health information not covered by HIPAA. (26) There are also ongoing efforts—including the National Science Foundation’s Safeguarding the Entire Community of the U.S. Research Ecosystem (SECURE) Center (27)—to ensure that data collected for research, including clinical trials, are secure. The proposed American Privacy Rights Act of 2024, first introduced to Congress in April 2024, aims to create a comprehensive framework to protect individuals’ privacy rights, including those related to health and other sensitive data. (28)

The Panel encourages continued discussion on this topic within and between all branches of the federal government. Mechanisms should be explored to protect patient data without obstructing data sharing and integration that support cancer care and research. The Panel recommends that Congress commission the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to evaluate the current regulatory landscape and provide guidance to legislators on next steps to improve policies to better serve patients.

Figure 6. mHealth Apps

* Healthcare providers are covered entities only if they transmit information in an electronic form in connection with a transaction for which HHS has adopted a standard. Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Transactions overview [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; n.d. [updated 2024 Aug 8; cited 2024 Sep 9]. [Available Online]