The communities most likely to experience health disparities are often also the ones with the least access to technology; (1) these disparities occur at both the individual and collective levels. Many patients in under-resourced communities lack access to computing devices beyond smartphones, but even households that can afford the latest devices cannot use them without crucial infrastructure like broadband internet, the absence of which can limit access to patient portals, participation in telehealth appointments, and the use of other tools. Adults over the age of 65, Black people, people with lower income and education, and those in rural communities are the least likely to have broadband access at home. (2)

The government approach to filling these gaps is complex and dispersed across numerous agencies and programs, including the Internet for All initiative. (3) While these efforts are commendable, some crucial programs lack consistent funding and implementation and are currently failing to reach large segments of the population.

Another barrier to accessing navigation and other medical care is privacy. In many communities, large households are common. Sharing a home may make it difficult to keep telehealth appointments and make private phone or video calls. Household members may also share devices, making it challenging for a patient to consistently use a device to access care. (4)

Recommendation 2.1: Provide sustainable funding for federal programs that facilitate access to broadband internet.

Access to broadband internet is significantly correlated with improved health outcomes. A 2019 report by the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC’s) Connect2Health Task Force found that broadband connectivity is a social determinant of health, akin to safe housing and clean air and water. (5) Because other social determinants of health such as education, job opportunities, and trainings are increasingly dependent on internet access, the Task Force deemed broadband connectivity a super determinant of health—a gateway to other activities that make a healthy life more possible. (6) Not surprisingly, limited broadband access is also linked to lower utilization of telehealth. (7)

Unfortunately, broadband internet access is currently out of reach for many Americans, particularly those in rural and inner-city communities. (2,8,9) This undermines health and makes it harder for people to take advantage of telehealth and other digital tools to access care. Ensuring equitable access to this crucial resource will require both short-term and long-term funding mechanisms. The Panel has identified two actions to support this goal.

Renew Funding for the Affordable Connectivity Program

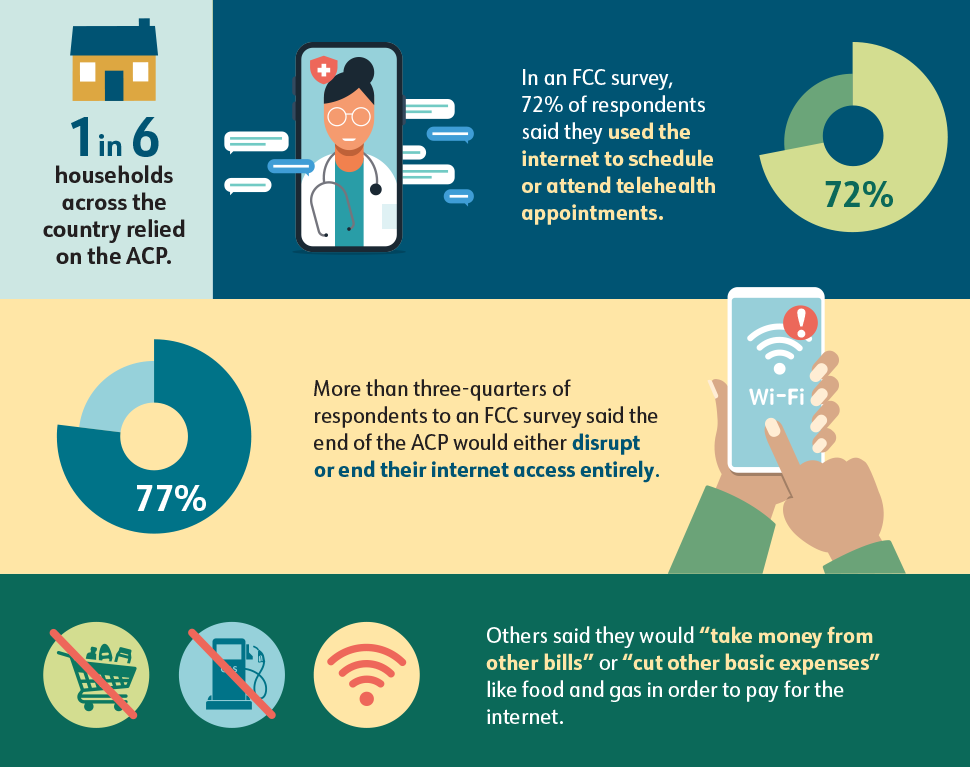

The FCC’s Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) provided crucial financial support to help households afford internet access, but funding for this program concluded in May 2024. (10)

The ACP was funded as part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and falls under the umbrella of the Internet for All initiative. (11) For years, the ACP provided eligible American households with a $30-per-month subsidy for high-speed internet service and a one-time subsidy of up to $100 for an internet-connected device.

The Program brought critical support to more than 23 million, or 1 in 6, households across the country (Figure 4). (12,13) In an FCC survey, 72% of respondents said they used the internet to schedule or attend telehealth appointments. Other top responses included looking for jobs, accessing government benefits, and doing schoolwork. In the months since funding for the ACP expired, these households have had to make difficult decisions. More than three-quarters of respondents to an FCC survey said the end of the ACP would either disrupt their internet access or end it entirely. Others said they would “take money from other bills” or “cut other basic expenses” like food and gas in order to pay for the internet. (14)

Bipartisan efforts to renew the Program have stalled, leaving millions of Americans with limited or no access to healthcare, work, school, and benefits.

The Panel recommends that Congress and the President renew funding for the Affordable Connectivity Program, with the understanding that a longer-term mechanism will be required to provide ongoing funds.

Figure 4. Affordable Connectivity Program

Reform the Universal Service Fund

The Universal Service Fund (USF), also overseen by the FCC, enhances telecommunication access in low-income areas. The Fund was created in response to the Communications Act of 1934, which stated that all people in the United States shall have access to rapid, efficient, nationwide communications service with adequate facilities at reasonable charges, and then expanded with the Telecommunications Act of 1996. (15)

The USF collects fees from telecommunications carriers, including wireline and wireless telephone companies, and interconnected Voice over Internet Protocol providers, including cable companies that provide voice service. Carriers are required by law to make contributions to the USF, paying a percentage of their end-user interstate and international revenues. The USF disburses funds through the Universal Service Administrative Company, while the FCC ensures rule compliance. (16,17)

The FCC established four programs within the USF: the Connect America Fund, to build broadband infrastructure in rural areas; Lifeline, for low-income consumers, including initiatives to expand telephone service on Tribal lands; Schools and Libraries (E-Rate), which makes telecommunications and information services more affordable for eligible schools and libraries; and Rural Health Care. The Rural Health Care program provides important funding for telecommunications and broadband internet to healthcare providers, such as medical schools, hospitals, and community health centers, but not directly to patients or consumers. (15)

The USF was created before the digital age and, consequently, is both limited and outdated, yet the mechanism has great potential to deliver service where it is needed most. Today, digital inclusion experts and the bipartisan Universal Service Fund Working Group in Congress are advocating for the modernization of this program. An updated version of the Fund could incorporate the collection of fees from internet service providers as well as heavy users of the networks like digital advertisers and content providers. (18)

Updating the Universal Service Fund to reflect the ways Americans consume and pay for telecommunications today could ensure sustainable funding not only for existing programs but for equitable broadband internet access through the ACP.

The Panel urges continued work by the Universal Service Fund Working Group and recommends that reformation of the Fund include ongoing support for the Affordable Connectivity Program.

Recommendation 2.2: Increase patient access to devices and private space through community sites to facilitate access to telehealth appointments.

Internet access is vital, but it is only part of the digital equity equation. Patients need internet-connected devices and private, secure settings to comfortably and effectively access telehealth appointments, patient portals, and health information. A practical and relatively low-lift solution to this need is to create dedicated telehealth spaces within public places in the community. (19) An effective telehealth space has four components:

- Privacy: a private room with a door or a soundproofed cubicle where a computer screen will not be visible to passersby

- Technology: an up-to-date desktop computer or other device that can support video calls, patient portal access, and other patient-facing technology needs

- Internet access: high-speed access to ensure an appointment will not be disrupted by outages or lagging audio or video

- Support: staff available to demonstrate how to use the space and to answer equipment-related questions as needed

Public libraries are a natural fit for this type of resource, as these settings already are oriented toward helping patrons meet their information needs, supplying computers and digital education, and providing private meeting spaces. Libraries are trusted anchors in their communities and are known as safe places to find information and get help, especially for those in need of social services or financial support.

The Network of the National Library of Medicine (NNLM) has led the charge to raise awareness of the need for and value of telehealth spaces in public libraries. NNLM’s Bridging the Digital Divide initiative and Telehealth Interest Group have designed courses and webinars and collaborated with libraries, healthcare providers, and other community institutions to implement the concept. Libraries across the United States have taken an interest in the idea, and telehealth programs are already under way at many sites. (19) One of the many benefits of this type of resource is its versatility; patrons and community members often need access to a private, internet-connected computer for non-health–related reasons. Labeling the private space a “meeting room” simultaneously increases the number of people who might benefit and eliminates any potential concerns about stigma related to being seen accessing healthcare.

Telehealth access points in public libraries may be funded through multiple mechanisms, including local, state, and federal funding. NNLM provides funding opportunities for libraries and library professionals to increase access to health information and improve equity. (20) At NCI, the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences supports healthcare delivery research and implementation. (21) The Panel encourages continued support of telehealth access efforts in libraries. Support should include funding for telehealth access spaces, outreach and education to libraries, and public training in digital skills. In addition, research should be done to evaluate the feasibility and impact of facilitating access to telehealth in libraries, and best practices in telehealth access methods and digital health literacy should be developed and disseminated.

Other community settings should also be considered as possible telehealth and digital healthcare access sites. Senior living facilities, housing shelters, and schools are trusted institutions accustomed to providing practical, technical, and health-related support for their residents, families, and visitors. Enabling private device access in these settings would offer a safe and convenient way for community members to meet their healthcare needs even amidst life changes or disruptions.

The federal Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program was created to support high-speed internet access and use in all 50 states, Washington, D.C.; Puerto Rico; the U.S. Virgin Islands; Guam; American Samoa; and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. (22) To date, all eligible entities have submitted Five-Year Action Plans, which will form the basis for how BEAD-allocated funds will be used. In addition, under the Digital Equity Act–funded State Digital Equity Planning Grant Program, each of the 56 eligible states and territories submitted a Digital Equity Plan. (23) Despite the established link between internet access and health disparities, the grant program did not require that plans include a health equity component. Once the Digital Equity Plans are accepted, states and territories will be able to apply for funds through the State Capacity Grant Program. As the BEAD and Digital Equity Act Programs move into the implementation and capacity-building phase, the Panel recommends that states and territories make access to telehealth a priority. (24)