Cancer screening has been shown to save lives and reduce the burden of cancer. However, gaps in cancer screening mean too many in the United States are unnecessarily enduring aggressive treatment or dying from cancers that could have been prevented or detected at earlier, more easily treated stages. This includes disproportionate numbers of socially and economically disadvantaged populations and many at elevated risk for cancer due to inherited mutations in cancer susceptibility genes. This avoidable burden of cancer imposes a heavy physical, emotional, and economic toll on individuals, families, and communities around the country. It also has broader economic implications, reducing workforce productivity and adding unnecessary strain to the healthcare system.

In 2020–2021, the President’s Cancer Panel held a series of meetings on cancer screening, with a focus on breast, cervical, colorectal, and lung cancers. The Panel concluded that more effective and equitable implementation of cancer screening represents a significant opportunity for the National Cancer Program, with potential to accelerate the decline in cancer deaths and, in some cases, prevent cancer through detection and removal of precancerous lesions. While continued research undoubtedly will lead to improvements in cancer screening in the coming years, meaningful gains can be made through better application of existing evidence-based modalities and guidelines.

Part 1: Cancer Screening in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities

Cancer screening has reduced the burden of cancer in the United States, but screening uptake has been incomplete and uneven. Furthermore, many people do not receive timely follow-up care after an abnormal screening test result, which undermines the effectiveness of screening. People without a usual source of care or health insurance, individuals with low income or low educational achievement, recent immigrants, individuals living in rural or remote areas, and members of some racial/ethnic minority groups are among those who experience disparities in cancer screening and follow-up care. Barriers to screening—which vary among individuals, communities, and healthcare settings—must be addressed to ensure that the benefits reach all populations.

Part 2: Taking Action to Close Gaps in Cancer Screening

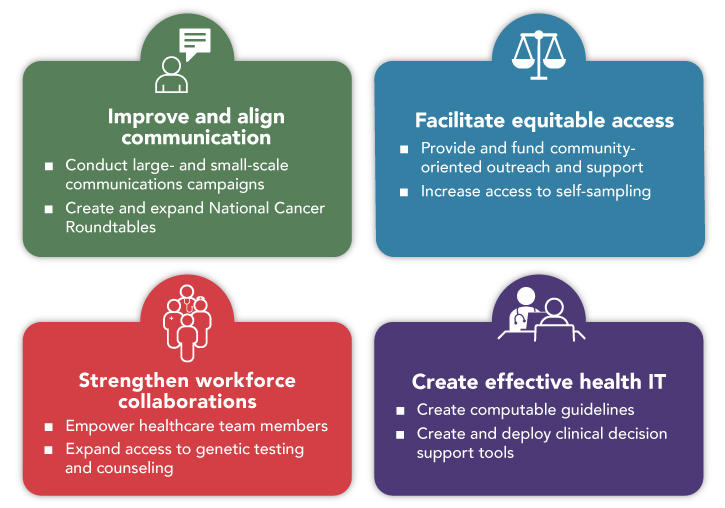

In this report, the Panel identifies four critical goals for connecting people, communities, and systems to improve equity and access in cancer screening. Implementation of the Panel’s recommendations to achieve these goals will improve communication, facilitate equitable access, promote team-based care, and harness technology to support patients and providers.

Goal 1: Improve and Align Cancer Screening Communication

The public and healthcare providers alike need accurate, digestible, and actionable information about cancer screening. Lack of knowledge and misconceptions about screening have been reported among many populations with low rates of cancer screening, including racial/ethnic minority groups, individuals with low income or low educational achievement, and populations with low access to healthcare.

Recommendation 1.1: Develop effective communications about cancer screening that reach all populations.

A renewed commitment to effective, targeted communications about cancer screening is needed to ensure that screening reaches all populations. Large and small organizations—including federal, state, and local government agencies; national advocacy organizations; healthcare systems; and community organizations—should develop and implement communications campaigns focused on cancer screening. These campaigns should emphasize the benefts of cancer screening—including improved prognosis associated with early detection and, in some cases, prevention of cancer—and the importance of regular screening. Communications about cancer screening should be developed and disseminated in ways that empower people to apply information to make decisions about their health and increase the likelihood they will adopt proven interventions. Targeted messaging is needed for each cancer type for which screening is available. These messages should be tailored to different populations, as needed, and designed to help individuals overcome identified barriers to optimal cancer screening.

Recommendation 1.2: Expand and strengthen National Cancer Roundtables that include a focus on cancer screening.

The Panel believes that the National Roundtable model provides an ideal framework for bringing stakeholders together and addressing gaps in cancer screening and follow-up care, including inequities experienced by various sociodemographic groups. The American Cancer Society (ACS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other key partners should invest resources to expand the National Roundtable model to increase coordination and promotion of high-quality cancer screening. New roundtables that include a strong focus on screening should be created for breast cancer and cervical cancer. Financial support for the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable and National Lung Cancer Roundtable should be increased to allow important work on colorectal and lung cancer screening to continue and expand their reach to communities with low rates of screening and follow-up care. National Roundtables should make health equity and alignment of messaging about cancer screening and cancer screening guidelines high priorities. Roundtable membership should represent the geographic, socioeconomic, and racial/ethnic diversity of the United States to ensure that the voices and perspectives of all populations inform activities and messaging.

Goal 2: Facilitate Equitable Access to Cancer Screening

Inadequate access to healthcare services due to geographic, financial, or logistical challenges is a commonly cited barrier to cancer screening. Fear of judgment, apprehension about potential diagnoses, cultural factors, lack of trust in healthcare systems, and structural racism also can deter people from seeking or receiving recommended care. These barriers contribute to the lower rates of cancer screening initiation and recommended follow-up observed among many.

Recommendation 2.1: Provide and sustainably fund community-oriented outreach and support services to promote appropriate screening and follow-up care.

Accessing and navigating healthcare systems can be daunting, particularly for populations that are medically underserved. Community health workers (CHWs) have invaluable expertise on the culture and life experiences of their communities, making them effective liaisons between those communities and healthcare systems. CHWs can perform a range of activities to promote cancer screening and appropriate follow-up care, facilitate access, and address inequities. Healthcare systems and health plans should establish CHW programs to reach the people in the communities they serve and ensure that those eligible receive appropriate and timely cancer screening and follow-up care. Healthcare systems and health plans should provide training directly or through partnerships with other organizations to ensure that CHWs have the knowledge and skills needed to do their jobs. To date, most CHW programs have been funded through short-term grants or contracts, which creates instability that undermines cultivation of meaningful relationships with communities, community members, and healthcare systems. Healthcare systems and health plans should establish sustainable funding for CHW programs to ensure they meet their full potential.

Recommendation 2.2: Increase access to self-sampling for cancer screening.

Self-sampling approaches can increase access to cancer screening for people who live long distances from medical facilities, have difficulty attending appointments, or are uncomfortable in medical settings or with medical procedures used for other screening approaches. For any screening done via self-sampling, patients who receive an abnormal result need to receive follow-up care at a healthcare facility. Screening, including screening with self-collected samples, is effective only if those screened receive appropriate and timely follow-up care.

Stool-based tests have been integrated into U.S. colorectal cancer screening guidelines; however, despite evidence they can increase screening uptake, they are underused. Healthcare providers should promote stool-based tests as an option for colorectal cancer screening, particularly for people who are hesitant or unable to undergo colonoscopy. In addition to offering colonoscopy, healthcare systems and health plans should distribute stool-based tests to individuals due for colorectal cancer screening as part of a systematic, organized effort to increase appropriate screening.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling has not been approved for use in the United States, although it has been used effectively in other countries. Evidence suggests that HPV self-sampling could help reach U.S. women who are underscreened for cervical cancer. The Panel encourages HPV test manufacturers to participate in validation efforts and pursue regulatory approval for HPV self-sampling strategies. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should prioritize review of the evidence supporting HPV self-sampling to ensure that it is available to women in the United States as soon as possible. If HPV self-sampling is approved by the FDA, U.S. cervical cancer screening programs, including state and federal programs, should use HPV self-sampling to extend the reach of cervical cancer screening.

Goal 3: Strengthen Workforce Collaborations to Support Cancer Screening and Risk Assessment

Providers play an essential role in patients’ decisions about whether and when to be screened for cancer. However, competing demands make it difficult to thoroughly address each patient’s needs within the limited time available during an appointment, particularly in the primary care setting in which most decisions about cancer screening are made.

Recommendation 3.1: Empower healthcare team members to support screening.

Team-based care has the potential to improve implementation of cancer screening. Healthcare systems and medical offices should set up systems and processes that allow all members of the healthcare team to promote and implement cancer screening programs or practices.

Payment policies can facilitate or restrict team-based care. Medicare coverage for lung cancer screening currently requires that the ordering physician or qualified nonphysician practitioner conducts a counseling and shared decision-making visit with the patient. This requirement places the burden of shared decision-making on the provider, introducing a bottleneck that results in a barrier to this new, lifesaving screening modality. If physicians can share the decision-making process with other team members, they will be able to implement lung cancer screening recommendations more broadly. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) should modify its coverage requirements to allow additional members of physician-led healthcare teams to conduct shared decision-making for lung cancer screening.

Recommendation 3.2: Expand access to genetic testing and counseling for cancer risk assessment.

Individuals at elevated risk for cancer due to their personal or family history or because they harbor mutations in cancer susceptibility genes may benefit from earlier, more frequent, or enhanced cancer screening or other risk-reducing interventions. Currently, most people with mutations in cancer susceptibility genes are never identified or are not identified until after they are diagnosed with cancer. Providers should regularly collect thorough family and personal health histories to determine whether their patients should undergo genetic testing for cancer risk genes.

Some payors require consultation with a certified genetic counselor or medical geneticist prior to genetic testing. Unfortunately, this policy creates an unnecessary barrier that results in fewer appropriate tests performed and longer turnaround times. Providers should be enabled to offer genetic testing with informed consent. Payors should eliminate requirements for pretest counseling by a certified genetic counselor or medical geneticist. Training and continuing education on genetics and genetic testing are critical to ensuring that providers are prepared to discuss various facets of genetic testing both before and after a patient undergoes testing. Training and residency programs, professional societies, guideline makers, and other organizations should expand opportunities for training and education on genetics, genetic testing, and interpretation of genetic testing results.

Genetic counselors are important members of the healthcare team. Most private insurers will reimburse certified genetic counselors who provide counseling services for people who meet personal and family history criteria for testing. However, genetic counselors are not recognized as healthcare providers by CMS, which means that they cannot be reimbursed directly through Medicare. Legislative changes should be made so that genetic counselors are recognized as healthcare providers by CMS. This would allow genetic counselors to contribute their specialized knowledge and skills to medical teams working to deliver high-quality care to patients at elevated risk for cancer and other diseases.

Goal 4: Create Health Information Technology that Promotes Appropriate Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening

Providers and patients alike are faced with more information than they can process in a reasonable amount of time. Health information technology (IT) has potential to help providers, patients, and healthcare systems quickly access and effectively use clinical knowledge and patient-specifc data. Suboptimal application of the evidence-based clinical practice guidelines—including guidelines for cancer risk assessment and screening—is a critical problem that should be addressed through health IT.

Recommendation 4.1: Create computable versions of cancer screening and risk assessment guidelines.

Before being incorporated into health IT tools—including clinical decision supports (CDS)—clinical guidelines must be converted into a format that can be fully interpreted and executed by a computer. Currently, each health IT developer using a guideline independently renders a computable representation. Public availability of all cancer risk assessment, screening, and follow-up guidelines in a computable format would promote broader, more consistent, and faster implementation. Research funding organizations with an interest in healthcare quality and implementation—including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), CDC, National Institutes of Health (NIH), ACS, and others—should fund development of computable guidelines for cancer risk assessment and screening. This could be done through grants to guideline organizations, researchers, or collaborative teams. CDC and AHRQ should consider investment in dedicated programs to support creation of computable guidelines relevant to risk assessment, screening, and follow-up care for cancer and other diseases. Computable guidelines should be shared through public resources, such as the AHRQ CDS Connect Repository, to facilitate their dissemination and use.

Recommendation 4.2: Create and deploy effective clinical decision support tools for cancer risk assessment and screening.

CDS can help providers and patients access and integrate clinical knowledge and patient-specific data to guide care. CDS may be particularly beneficial for primary care providers, who are expected to address a wide range of issues within a limited time during appointments, and providers in settings with limited financial resources. To be effective, CDS must deliver the right information in the right formats through the right channels to the right people at the right times in clinical workflows. Electronic health record (EHR) vendors, healthcare organizations, and research funding organizations—including AHRQ, NIH, CDC, and private foundations—should prioritize support for development and evaluation of standards-based, interoperable CDS for cancer risk assessment and screening. CDS should be integrated with EHRs to optimize workflow, facilitate data exchange, and avoid duplicate data entry. EHR vendors should include CDS for cancer risk assessment and screening in standard EHR systems and make it as easy as possible for CDS developed by others to be integrated with the EHR. To this end, it is critical that EHR vendors and IT developers continue to pursue interoperability of health IT systems.

Part 3: Conclusions

More effective and equitable implementation of cancer screening can save lives and reduce the burden of cancer. Implementation of the goals and recommendations put forth in this report will help optimize cancer screening through better communication about cancer risk and screening, enhanced access to care, and more efficient application of evidence-based screening guidelines. The Panel urges all stakeholders—healthcare providers, healthcare systems, payors, community and patient advocacy organizations, government agencies, and individuals—to work together to close gaps in cancer screening and ensure that the benefits reach all populations.