Part 1:

The Rising Cost of Cancer Drugs: Impact on Patients and Society

Advances from basic science in understanding the molecular underpinnings of cancer and lessons from the clinical and population sciences are creating new opportunities to treat many cancer types effectively to produce extended remissions and, ultimately, cures. Biopharmaceutical companies are contributing to and capitalizing on this new knowledge. Several new therapies already have changed the cancer treatment landscape. The number of oncology drugs under development—also referred to as the oncology drug pipeline—grew by 63 percent between 2005 and 2015,1 raising hopes that even more effective, potentially curative treatments are on the horizon. However, spending on cancer drugs has strained patient and societal resources and is a major cause for concern, particularly since the number of cancer cases is expected to rise as the U.S. population ages.2 The United States faces the challenge and tension of creating both a robust pipeline of innovative cancer drugs while ensuring that these drugs are accessible and affordable for those who need them.

Cancer Drug Prices Are Increasing

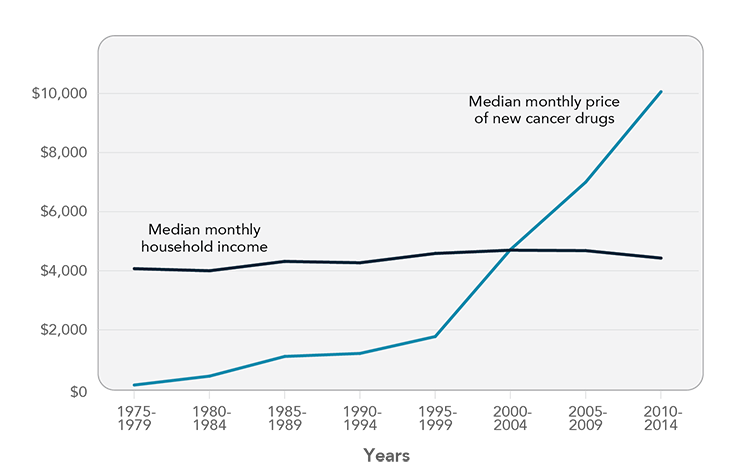

Remarkable scientific innovation has produced a growing number of immunotherapies and molecularly targeted therapies over the past couple of decades. Over the same time period, launch prices of cancer drugs in the United States have increased dramatically, vastly outpacing growth in household incomes since 1975 (Figure 1). There are no signs that this price escalation is slowing. Over half of new cancer drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration between 2009 and 2013 were priced at more than $100,000 per patient for a year of treatment.3 In 2015, new cancer drugs ranged in price from $7,484 to $21,834 per patient per month.4

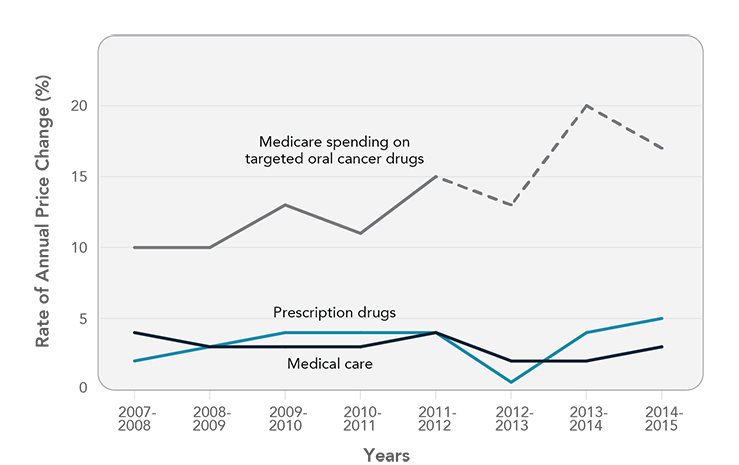

Drugs account for about 20 percent of the total costs of cancer care, but cancer drug costs are accelerating faster than costs for other components of care. While total cancer care costs increased about 60 percent for commercially insured cancer patients between 2004 and 2014, spending on cytotoxic and biologic chemotherapies grew by 101 and 485 percent, respectively, over the same timeframe.5 In addition, annual Medicare spending on targeted oral cancer drugs has increased dramatically, outpacing price increases for medical care and prescription drugs overall (Figure 2).6 Increased spending is the result of higher drug prices, greater use of high-priced drugs, and an increase in the proportion of chemotherapy infusions being done in hospital outpatient settings, which is generally more expensive than administering drugs in physicians’ offices.5,7

Some new cancer drugs have been transformative—significantly improving patients’ outcomes and, in some cases, producing long-term remissions (see Imatinib: Case Study of a Generic Cancer Drug in Recommendation 4).8 Innovative new therapies—such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies9,10—also have potential to extend survival for many more patients. High prices may be warranted for drugs that significantly extend survival and/or substantially improve quality of life. Many new cancer drugs, however, do not provide clinically meaningful improvements as defined by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.11 U.S. patients and their insurers are paying more than ever for cancer drugs—$54,100 for a year of life in 1995 compared with $207,000 in 201312—but survival gains for most drugs still are measured in months.11 Prices are similarly high for novel drugs and the “me-too” drugs that often follow,3,13 and prices often increase substantially after launch.14 Market entry of generic drugs has not reliably provided relief from high prices.15-17 The emergence of combination therapies that include more than one high-priced drug will exacerbate the problem.18

Figure 1

Launch Price of New Cancer Drugs Compared with Household Income, 1975-2014

Source: Prasad V, Jesus K, Mailankody S. The high price of anticancer drugs: origins, implications, barriers, solutions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28290490

Figure 2

Price Changes for Targeted Oral Cancer Drugs, Medical Care, and Prescription Drugs, 2007-2015

Note: Graph based on gross Medicare drug costs per patient per month. Dashed line represents projection on the basis of data published by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medical care and prescription drug data are based on Consumer Price Index data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Source: Shih YT, Xu Y, Liu L, Smieliauskas F. Rising prices of targeted oral anticancer medications and associated financial burden on Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(22):2482-9. Reprinted with permission. © 2018 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28471711

The Toll of Drug Costs on Patients and Their Families

The burden of high drug costs on patients—even those with health insurance—can be significant. Out-of-pocket spending on drugs can be hundreds, or even thousands, of dollars a month for patients in active treatment.6,7,19 Many patients are paying more for their drugs as insurance plans increasingly are charging coinsurance—a percentage of a drug’s cost—rather than fixed copayments for prescription drugs.20-23 As drugs extend survival, more patients are taking high-priced drugs for months, or even years, which may create long-term financial hardship. Patients with higher out-of-pocket expenses are less likely to adhere to recommended treatment regimens, which may have a detrimental impact on outcomes.24-28

Although out-of-pocket expenses for drugs can be high, they are only one of many costs cancer patients face. Costs of other components of care—surgery, radiation, hospitalization, and clinic visits—each often represent a higher share of treatment costs than drugs.29,30 Many patients and their families and caregivers also experience indirect costs related to loss of income, and transportation and childcare costs, among other expenses.31 Collectively, these costs can impose a significant burden on patients. Many cancer patients incur considerable debt as a result of their treatments32 and/or reduce spending on basic necessities to defray out-of-pocket expenses.33

The term financial toxicity describes the negative impact of cancer care costs on patients’ well-being (see Financial Toxicity in Recommendation 3). Like medical toxicities caused by cancer treatment, financial toxicity can significantly diminish patients’ quality of life, interfere with high-quality care delivery, and even reduce survival rates.34-38

Action Is Needed to Ensure Patients’ Access to High-Value Drugs

Drug development is an expensive and high-risk undertaking. While estimates vary widely, one recent study estimated the cost of developing a new drug at $2.6 billion,39 and only 1 in 15 oncology drugs studied in Phase 1 clinical trials will make it to market.40 Biopharmaceutical companies cannot be expected to incur the high costs of development without the potential for achieving financial benefits, including recovery of research and development costs, when drugs provide high value to patients. This is part of the cycle that drives future innovation. While drug developers should be rewarded financially for creating innovative drugs that provide high value to patients, it also is important that drugs are affordable and accessible for patients and society.

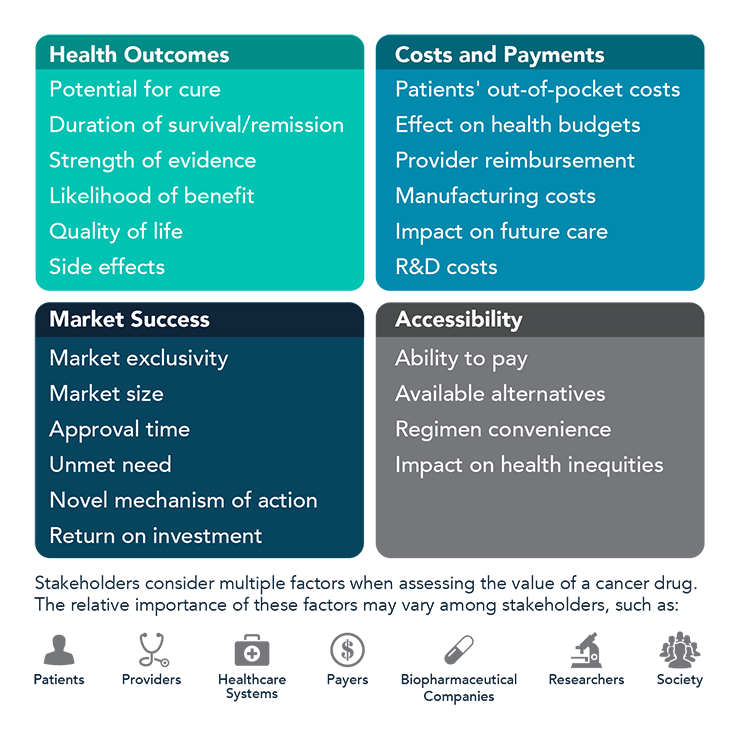

The President’s Cancer Panel held a series of workshops in 2016-2017 to investigate the causes and consequences of rising cancer drug prices in the United States. During the series and in this report, drugs are defined broadly to include small molecules, biologics, and immunotherapies. The Panel concluded that misalignment of drug prices and value is a critical problem that must be addressed. The costs of drugs should reflect the value to those who receive treatment—patients. Defining the value of cancer drugs is challenging. Numerous factors influence value, and the relative importance of each of these factors depends on the perspective of the stakeholders—patients, providers, payers, healthcare systems, manufacturers, researchers, and society (Figure 3).41 Though the needs of all stakeholders should be considered, patient benefit must be central when assessing value. In this report, the Panel makes several recommendations to maximize value and affordability while continuing to support a pipeline of biopharmaceutical innovation. The ultimate goal is to ensure that all cancer patients—now and in the future—have affordable access to high-value drugs without experiencing financial toxicity.

Figure 3

Factors That Influence Cancer Drug Value

References

- IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Global oncology trend report: a review of 2015 and outlook to 2020. Parsippany (NJ): IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics; 2016 Jun. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/global-oncology-trend-report-2016.pdf

- Weir HK, Thompson TD, Soman A, Moller B, Leadbetter S. The past, present, and future of cancer incidence in the United States: 1975 through 2020. Cancer. 2015;121(11):1827-37. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25649671

- Mailankody S, Prasad V. Five years of cancer drug approvals: innovation, efficacy, and costs. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):539-40. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26181265

- Bach PB. Cancer drug costs for a month of treatment at initial Food and Drug Administration approval. New York (NY): Center for Health Policy & Outcomes, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; 2017. Available from: https://www.mskcc.org/research-areas/programs-centers/health-policy-outcomes/cost-drugs

- Fitch K, Pelizzari PM, Pyenson B. Cost drivers of cancer care: a retrospective analysis of Medicare and commercially insured population claim data 2004-2014. Milliman (commissioned by the Community Oncology Alliance); 2016 Apr. Available from: http://www.milliman.com/insight/2016/Cost-drivers-of-cancer-care-A-retrospective-analysis-of-Medicare-and-commercially-insured-population-claim-data-2004-2014

- Shih YT, Xu Y, Liu L, Smieliauskas F. Rising prices of targeted oral anticancer medications and associated financial burden on Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(22):2482-9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28471711

- Shih YC, Smieliauskas F, Geynisman DM, Kelly RJ, Smith TJ. Trends in the cost and use of targeted cancer therapies for the privately insured nonelderly: 2001 to 2011. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(19):2190-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25987701

- Howard DH, Chernew ME, Abdelgawad T, Smith GL, Sollano J, Grabowski DC. New anticancer drugs associated with large increases in costs and life expectancy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1581-7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27605636

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approval brings first gene therapy to the United States [News Release]. Silver Spring (MD): FDA; 2017 Aug 30. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm574058.htm

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves CAR-T cell therapy to treat adults with certain types of large B-cell lymphoma [News Release]. Silver Spring (MD): FDA; 2017 Oct 18. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm581216.htm

- Kumar H, Fojo T, Mailankody S. An appraisal of clinically meaningful outcomes guidelines for oncology clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(9):1238-40. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27281466

- Howard DH, Bach PB, Berndt ER, Conti RM. Pricing in the market for anticancer drugs. J Econ Perspect. 2015;29(1):139-62. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28441702

- Fojo T, Mailankody S, Lo A. Unintended consequences of expensive cancer therapeutics-the pursuit of marginal indications and a me-too mentality that stifles innovation and creativity: the John Conley Lecture. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(12):1225-36. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25068501

- Bennette CS, Richards C, Sullivan SD, Ramsey SD. Steady increase in prices for oral anticancer drugs after market launch suggests a lack of competitive pressure. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):805-12. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27140986

- Kantarjian H. The arrival of generic imatinib into the U.S. market: an educational event. The ASCO Post [Internet]. 2016 May 25 [cited 2017 Jun 23]. Available from: http://www.ascopost.com/issues/may-25-2016/the-arrival-of-generic-imatinib-into-the-us-market-an-educational-event

- Cole AL, Sanoff HK, Dusetzina SB. Possible insufficiency of generic price competition to contain prices for orally administered anticancer therapies. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1679-80. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28892541

- Gupta R, Kesselheim AS, Downing N, Greene J, Ross JS. Generic drug approvals since the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1391-3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27428055

- Ramsey S. Drug pricing should depend on shared values. Nature. 2017;552(21):S78. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29293242

- Hoadley J, Cubanski J. It pays to shop: variation in out-of-pocket costs for Medicare Part D enrollees in 2016. Menlo Park (CA): The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2015 Dec. Available from: http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-It-Pays-to-Shop-Variation-in-Out-of-Pocket-Costs-for-Medicare-Part-D-Enrollees-in-2016

- Pearson CF, Carpenter E, Sloan C. Consumer costs continue to increase in 2017 exchanges [Press Release]. Washington (DC): Avalere; 2017 Jan 18. Available from: http://avalere.com/expertise/life-sciences/insights/consumer-costs-continue-to-increase-in-2017-exchanges

- Pearson CF. Majority of drugs now subject to coinsurance in Medicare Part D plans [Press Release]. Washington (DC): Avalere; 2016 Mar 10. Available from: http://avalere.com/expertise/managed-care/insights/majority-of-drugs-now-subject-to-coinsurance-in-medicare-part-d-plans

- Danzon PM, Taylor E. Drug pricing and value in oncology. Oncologist. 2010;15(1 Suppl):24-31. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20237214

- American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. ACS CAN examination of cancer drug coverage and transparency in the health insurance marketplaces. Atlanta (GA): ACS CAN; 2017 Feb 22. Available from: https://www.acscan.org/sites/default/files/National%20Documents/QHP%20Formularies%20Analysis%20-%202017%20FINAL.pdf

- Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, Johnsrud M. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(3 Suppl):46s-51s. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21886519

- Shen C, Zhao B, Liu L, Shih YT. Adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors among Medicare Part D beneficiaries with chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer. [Epub 2017 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28976559

- Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(4):306-11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24366936

- Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, Chino F, Samsa GP, Altomare I, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(3):162-7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24839274

- Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, Stratton S, Brouse CH, Hillyer GC, et al. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2534-42. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21606426

- Narang AK, Nicholas LH. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(6):757-65. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27893028

- Dieguez G, Ferro C, Pyenson B. A multi-year look at the cost burden of cancer care. Seattle (WA): Milliman; 2017 Apr 11. Available from: http://www.milliman.com/insight/2017/A-multi-year-look-at-the-cost-burden-of-cancer-care

- American Cancer Society. The costs of cancer. Atlanta (GA): ACS; 2017 Apr 11. Available from: https://www.acscan.org/policy-resources/costs-cancer

- Banegas MP, Guy GP Jr, de Moor JS, Ekwueme DU, Virgo KS, Kent EE, et al. For working-age cancer survivors, medical debt and bankruptcy create financial hardships. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):54-61. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26733701

- Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, Taylor DH, Goetzinger AM, Zhong X, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381-90. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23442307

- Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure—out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1484-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24131175

- Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, Part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(2):80-1, 149. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23530397

- Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among U.S. cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122(8):283-9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26991528

- PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Financial toxicity and cancer treatment [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; [updated 2016 Dec 14; cited 2017 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/managing-care/track-care-costs/financial-toxicity-hp-pdq

- Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough DK, Overstreet KA, Shankaran V, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26811521

- DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG, Hansen RW. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: new estimates of R&D costs. J Health Econ. 2016;47:20-33. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26928437

- Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosenthal J. Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(1):40-51. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24406927

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Making medicines affordable: a national imperative. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2017 Nov. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24946