Goal 1: Reduce Missed Clinical Opportunities to Recommend and Administer the HPV Vaccine

CDC, AAP, AAFP, and others have effectively promoted HPV vaccination through provider education, training, and resource development.

In its 2012-2013 report, the Panel recommended development of communication strategies and systems changes to ensure that all eligible adolescents and young adults were offered the HPV vaccine when they visited their healthcare providers. Since that time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched a multipronged campaign aimed at improving clinicians’ practices, recognizing HPV vaccine champions, and supporting health systems (see Improving Providers’ Recommendations).1-3 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and other health professional associations have urged their members to recommend vaccination strongly and developed resources to support increases in uptake (see Professional Organizations Urge Strong Recommendations).4-8 Several interventions targeting provider HPV vaccine knowledge and practices also have been developed.9,10

Improving Providers’ Recommendations

CDC has developed several resources—including videos—that coach providers on the best way to recommend HPV vaccination.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Improving your HPV vaccine recommendation—suggestions from Dr. Todd Wolynn [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2018 Jan 4 [cited 2018 Sep 4]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XnlkcJyWwvo

Professional Organizations Urge Strong Recommendations

In 2014, several health professional organizations—the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and American College of Physicians—partnered with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Immunization Action Coalition to urge their members to firmly and strongly recommend HPV vaccination to their patients. Many providers reported improving their HPV vaccine communication after receiving information from their professional organizations.

Sources: American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Physicians, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Immunization Action Coalition. Letter to: Colleagues 2014. Available from: http://www.immunize.org/letter/recommend_hpv_vaccination.pdf; Hswen Y, Gilkey MB, Rimer BK, Brewer NT. Improving physician recommendations for human papillomavirus vaccination: the role of professional organizations. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(1):42-7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27898573

The commitment of these groups and the efforts of many healthcare providers undoubtedly have contributed to increases in HPV vaccination observed in recent years. Their roles in progress achieved to date should be commended. Yet, too many adolescents continue to leave their doctors’ offices without receiving the HPV vaccine, even when they have received other recommended vaccines.11-14 One study of girls who had not received the HPV vaccine by 13 years of age found that 80 percent had had healthcare encounters during which another vaccine was administered.12 If the HPV vaccine had been given at all of these visits, HPV vaccine initiation rates would have reached nearly 90 percent. The Panel Chair emphasizes strongly that provider- and systems-level changes hold the greatest potential for eliminating missed clinical opportunities, normalizing HPV vaccination, and ensuring that U.S. adolescents and future generations are optimally protected from HPV cancers.15

Strong Provider Recommendations Are Needed

Provider recommendation is one of the strongest predictors of adolescent HPV vaccine uptake, even stronger than often-studied factors such as race/ethnicity, insurance status, knowledge of HPV, and perceptions about HPV vaccine effectiveness and safety.16,17 Most physicians who provide care for adolescents say they recommend HPV vaccination,18,19 and surveys of parents suggest that providers are more likely to recommend the HPV vaccine now than in the past.20,21 However, too many parents of age-eligible adolescents do not recall receiving a recommendation from their children’s healthcare providers.17,20,21

How the vaccine is recommended is important. Studies have found that providers often deliver weak or unclear recommendations for the HPV vaccine (e.g., presenting the vaccine as being optional, less important, or less urgent than other adolescent vaccines).16,17,22,23 These recommendations may be sufficient for parents who already hold favorable views of HPV vaccination, but they are less likely to convince parents who have questions or uncertainties to vaccinate their adolescents.

CDC urges providers to deliver a clear, concise, and strong recommendation for same-day HPV vaccination.1 The vaccine’s efficacy in preventing cancer should be emphasized.17 Children of parents who received high-quality recommendations aligned with these guidelines are more likely to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series than those of parents who received a low-quality or no recommendation.17 The Panel Chair urges healthcare providers to strongly recommend HPV vaccination for all eligible adolescents. Recommendations are most likely to be effective if providers:

- Use announcement language. Brief statements that assume parents are ready to vaccinate are associated with higher vaccine uptake than are open-ended, conversational approaches.24-27 Announcements may be particularly effective for parents who are ambivalent or uncertain about HPV vaccination because these types of statements present vaccination as the social norm and affirm the provider’s confidence in safety and effectiveness of the vaccine.15 Open-ended discussions should be reserved for instances in which parents raise specific questions or concerns.

- Bundle with other adolescent vaccines. The HPV vaccine should be recommended at the same time and in the same way as other recommended adolescent vaccines, with HPV cancer prevention in the middle of the list (your son/daughter is due for vaccinations to help protect him/her from meningitis, HPV cancers, and whooping cough).1,28

- Focus on vaccination of young adolescents. Although ACIP recommends routine HPV vaccination of 11- and 12-year-olds, providers are more likely to recommend the vaccine strongly to older adolescents.17 Providers should strongly recommend same-day HPV vaccination for all of their 11- and 12-year-old patients unless it is contraindicated. If parents suggest delaying vaccination, providers should emphasize that the vaccine is most effective when administered well before HPV exposure.29 Additionally, younger adolescents exhibit strong immune responses following vaccination,30 and those who initiate the series before 15 years of age require only two doses instead of three. Providers also should recommend the vaccine to older adolescents and young adults who have not completed the recommended series.

- Promote vaccination of boys and girls equally. Providers are less likely to consistently and strongly recommend HPV vaccination of boys than of girls,17-19 and parents of boys are more likely than those of girls to cite lack of provider recommendation as a reason for nonvaccination.20,21 Providers should deliver strong recommendations for both girls and boys to ensure that recent increases in vaccine coverage among boys continue. Males account for a growing proportion of HPV cancers in the United States due to the increasing incidence of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers.31-33

- Repeat recommendations as needed. Some parents respond to a provider’s recommendation with hesitance or refusal. Many of these parents will decide to vaccinate their children at the same visit if providers persist in identifying and addressing parents’ questions and concerns, reemphasize the importance of the vaccine, and restate the recommendation.34 Furthermore, a significant proportion of parents who initially decline HPV vaccination will accept it at a future visit. One study found that provider recommendations, particularly high-quality recommendations, played an important role in subsequent vaccine acceptance.35

CDC and health professional organizations (e.g., AAP, AAFP) should continue to promote strong, clear provider recommendations for HPV vaccination. CDC should continue to develop and provide resources to support providers. Studies have found that providers in rural areas are less likely to recommend the vaccine,36,37 and family physicians are somewhat less likely than pediatricians to consistently and strongly recommend the HPV vaccine.18,19,38 Increasing the quality of recommendations delivered in rural settings, which are commonly served by family practice physicians,39 may increase low vaccination rates observed in many rural areas. Continued monitoring also is needed to ensure that vaccine financing issues (e.g., provider concerns about upfront costs of the vaccine, inadequate reimbursement) do not interfere with access to the HPV vaccine or create disincentives for strong provider recommendations.

Systems-Level Efforts Facilitate Vaccination

Systems-level policies and practices have potential to drive substantial, enduring improvements in HPV vaccination rates by minimizing missed clinical opportunities, facilitating vaccine access, and promoting acceptance and normalization of the vaccine. Clinical practices, healthcare systems, and public health departments should identify and adopt strategies to increase their HPV vaccination rates. Programs that implement multiple strategies are more likely to be successful.9 Analyses of successful programs and experiences with other vaccines and cancer prevention and screening recommendations have identified several evidence-based approaches to promote HPV vaccination, including:9,10,15,38,40-50

- Conduct training. Providers should be trained to deliver strong recommendations and address common parent questions and concerns, including those about safety.

- Engage all office staff in vaccination efforts. All office staff who interface with patients should be trained to ensure consistent, positive messaging about the vaccine. A vaccine champion and quality improvement team can foster a provaccination culture and promote positive change.

- Use a tracking system. It is critical to reliably identify patients due or overdue for vaccination and monitor vaccination rates. Tracking systems can be embedded within or integrated with electronic health records (EHRs). Integration with state immunization information systems (IIS) would enhance tracking capacity.

- Prompt healthcare providers. Clinicians should be informed when a patient is due or overdue for HPV vaccination. Prompts can be automatically generated by EHR systems or manually noted based on review of patients’ charts prior to their appointments.

- Implement standing orders. Standing orders, which allow nurses or other medical personnel to administer vaccines using an established protocol without a direct order from a physician, increase vaccination rates in many settings.

- Send reminders. Parents should be informed when their children are due for a vaccine dose. One or more effective reminder methods can be used (e.g., phone, letter, email, text, EHR-based message), an approach that can be especially effective when handled in a centralized way.

- Facilitate access. Providing walk-in or immunization-only appointments can make it easier for patients to receive the vaccine, particularly second or third doses. The vaccine should be offered opportunistically at all types of appointments unless contraindicated (e.g., well child, sick child, sports physicals).

- Implement quality improvement initiatives. Provider-, clinic-, and systems-level vaccination rates should be monitored and shared to provide accountability and incentivize improvement. Education and quality improvement programs focused on HPV vaccination could be implemented to meet requirements for board certification (i.e., Maintenance of Certification; see Quality Improvement Initiative Improves HPV Vaccine Initiation and Completion).

Quality Improvement Initiative Improves HPV Vaccine Initiation and Completion

The American Cancer Society’s HPV Vaccinate Adolescents Against Cancers (VACs) program partners with primary care practices, health plans, hospital systems, and state entities to strengthen regional HPV vaccination efforts. Quality improvement (QI) partnerships are a core focus of the program. In 2017, VACs staff engaged Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) in evidence-based QI interventions, including an intensive learning collaborative that awarded Maintenance of Certification and Continuing Medical Education credits. About 40 participating FQHCs, comprising 119 clinic sites, increased their HPV vaccine series initiation rates by an average of 16 percentage points. Series completion rates rose by 18 percentage points, on average.

Source: American Cancer Society. HPV Vaccinate Adolescents Against Cancers: activity and impact report, 2017-2018. Atlanta (GA): ACS; 2018. Available from: https://www.mysocietysource.org/sites/HPV/ResourcesandEducation/CDC%20Annual%20Report%20%20Test/2018/VACs%202017-2018%20Activity%20and%20Impact%20Report.pdf

The Panel Chair urges health system leaders to make HPV vaccination a high, measurable priority. Implementation of systems changes within large health systems could facilitate HPV vaccination of large numbers of adolescents and potentially increase overall vaccine coverage rates within geographic regions served. Some health systems already have established systems-level processes to support HPV vaccination, resulting in coverage rates well above the national average (see Rapid Adoption of the HPV Vaccine within a Health System).38,40 Clinics and health systems should use resources shown to be effective in increasing HPV vaccination. These include resources developed by organizations such as the CDC,2,51 AAP,8 the American Cancer Society,28 and the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.52,53 Advocacy organizations, health professional organizations, state vaccine coalitions, National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers, and state health officials should engage health systems within their regions to encourage prioritization of HPV vaccination and implementation of practices and policies to increase coverage rates.

The updated HEDIS measure for adolescent vaccines promotes bundling of HPV with other recommended vaccines.

Clinics and healthcare systems are motivated by quality metrics established by external bodies. Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measures are used as the basis of health plan accreditation by the National Committee for Quality Assurance and are used by health plans themselves to drive improvements in quality of care and services.54 The updated measure for adolescent immunizations in HEDIS 2017 assesses the proportion of all adolescents who receive all recommended vaccines (meningococcal, Tdap, HPV) by their thirteenth birthdays.55 This should provide incentives for providers and healthcare systems to bundle their recommendations for all adolescent vaccines and may help raise HPV vaccine coverage to the level of the other vaccines.

The Healthy People 2020 goal for HPV vaccines now includes both girls and boys.

The 2014 addition of a Healthy People 2020 goal focused on males may encourage gender-neutral vaccination.56 The Panel Chair agrees with the National Vaccine Advisory Committee that the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) should include a measure for HPV vaccination of adolescents in the Uniform Data System, the required reporting system for HRSA grantees in community health centers, migrant health centers, health centers for homeless grantees, and public housing primary care organizations.57

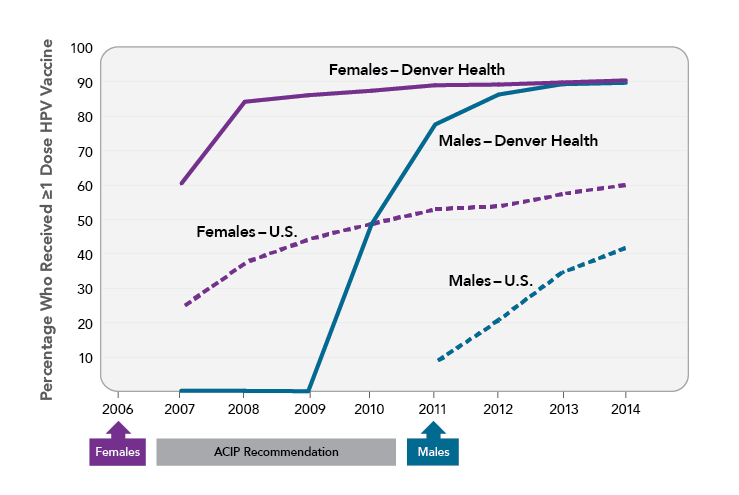

Rapid Adoption of the HPV Vaccine within a Health System

Denver Health, an integrated urban safety net health system that serves more than 17,000 adolescents each year, has implemented several processes to facilitate vaccine uptake. The internally developed immunization registry (VaxTrax) creates a list of vaccines for which each patient is due. Vaccines are offered at every visit (even if they were previously declined), and providers are encouraged to bundle all adolescent vaccines together when recommending them. Standing orders allow adolescent vaccines, including the HPV vaccine, to be administered by a medical assistant. These processes contributed to rapid uptake of the HPV vaccine within Denver Health clinics. By 2014, nearly 90 percent of girls and boys (ages 13-17) had received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine. In contrast, national rates for 13- to 17-year-old girls and boys in 2014 were 60 percent and 42 percent, respectively.

Sources: Farmar AM, Love-Osborne K, Chichester K, et al. Achieving high adolescent HPV vaccination coverage. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27940751; Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):909-17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30138305

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Talking to parents about HPV vaccine [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [updated 2018 Apr 30; cited 2018 May 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/for-hcp-tipsheet-hpv.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tools and materials for your office [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [updated 2017 Mar 10; cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/tools-materials.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccine Is Cancer Prevention Champion [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [updated 2017 Oct 25; cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/champions/index.html

- American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, et al. Letter to: Colleagues 2014. Available from: http://www.immunize.org/letter/recommend_hpv_vaccination.pdf

- Hswen Y, Gilkey MB, Rimer BK, Brewer NT. Improving physician recommendations for human papillomavirus vaccination: the role of professional organizations. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(1):42-7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27898573

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Immunizations [Internet]. Itasca (IL): AAP; [cited 2018 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/immunizations/Pages/HPV.aspx

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV) [Internet]. Leawood (KS): AAFP; [cited 2018 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/public-health/immunizations/disease-population/hpv.html

- American Academy of Pediatrics. HPV vaccine is cancer prevention [Internet]. Itasca (IL): AAP; [cited 2018 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/immunizations/HPV-Champion-Toolkit/Pages/Making-a-Change-in-Your-Office.aspx

- Smulian EA, Mitchell KR, Stokley S. Interventions to increase HPV vaccination coverage: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1566-88. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26838959

- Walling EB, Benzoni N, Dornfeld J, et al. Interventions to improve HPV vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27296865

- Kepka D, Spigarelli MG, Warner EL, et al. Statewide analysis of missed opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccination using vaccine registry data. Papillomavirus Res. 2016;2:128-32. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27540595

- Jeyarajah J, Elam-Evans LD, Stokley S, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among girls before 13 years: a birth year cohort analysis of the National Immunization Survey-Teen, 2008-2013. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55(10):904-14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26603581

- Espinosa CM, Marshall GS, Woods CR, et al. Missed opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccine initiation in an insured adolescent female population. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6(4):360-5. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29036336

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):909-17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30138305

- Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, et al. Increasing vaccination: putting psychological science into action. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18(3):149-207. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29611455

- Dempsey AF, O'Leary ST. Human papillomavirus vaccination: narrative review of studies on how providers' vaccine communication affects attitudes and uptake. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S23-7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29502633

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, et al. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34(9):1187-92. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26812078

- Finney Rutten LJ, St Sauver JL, Beebe TJ, et al. Association of both consistency and strength of self-reported clinician recommendation for HPV vaccination and HPV vaccine uptake among 11- to 12-year-old children. Vaccine. 2017;35(45):6122-8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28958810

- Allison MA, Hurley LP, Markowitz L, et al. Primary care physicians' perspectives about HPV vaccine. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20152488. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26729738

- Thompson EL, Rosen BL, Vamos CA, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination: what are the reasons for nonvaccination among U.S. adolescents? J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(3):288-93. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28842066

- Hanson KE, Koch B, Bonner K, et al. National trends in parental HPV vaccination intentions and reasons for hesitancy, 2010-2015. Clin Infect Dis. [Epub 2018 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29596595

- Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, et al. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1673-9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26494764

- Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1454-68. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26838681

- Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, et al. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1037-46. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24190677

- Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, et al. The influence of provider communication behaviors on parental vaccine acceptance and visit experience. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):1998-2004. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25790386

- Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, et al. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27940512

- Malo TL, Hall ME, Brewer NT, et al. Why is announcement training more effective than conversation training for introducing HPV vaccination? A theory-based investigation. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):57. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29673374

- American Cancer Society. Steps for increasing HPV vaccination in practice: an action guide to implement evidence-based strategies for clinicians. Atlanta (GA): ACS; 2016. Available from: http://hpvroundtable.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Steps-for-Increasing-HPV-Vaccination-in-Practice.pdf

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-05):1-30. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25167164

- Dobson SR, McNeil S, Dionne M, et al. Immunogenicity of 2 doses of HPV vaccine in younger adolescents vs 3 doses in young women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309(17):1793-802. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23632723

- Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29):3235-42. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26351338

- D'Souza G, Wentz A, Kluz N, et al. Sex differences in risk factors and natural history of oral human papillomavirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(12):1893-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26908748

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers—United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):918-24. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30138307

- Shay LA, Baldwin AS, Betts AC, et al. Parent-provider communication of HPV vaccine hesitancy. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172312. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29765009

- Kornides ML, McRee AL, Gilkey MB. Parents who decline HPV vaccination: who later accepts and why? Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S37-S43. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29502636

- Henry KA, Swiecki-Sikora AL, Stroup AM, et al. Area-based socioeconomic factors and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among teen boys in the United States. BMC Public Health. 2017;18(1):19. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28709420

- Warner EL, Ding Q, Pappas L, et al. Health care providers' knowledge of HPV vaccination, barriers, and strategies in a state with low HPV vaccine receipt: mixed-methods study. JMIR Cancer. 2017;3(2):e12. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28801303

- Irving SA, Groom HC, Stokley S, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage and prevalence of missed opportunities for vaccination in an integrated healthcare system. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S85-S92. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29502643

- Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG. Physicians and rural America. West J Med. 2000;173(5):348-51. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11069878

- Farmar AM, Love-Osborne K, Chichester K, et al. Achieving high adolescent HPV vaccination coverage. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27940751

- Lollier A, Rodriguez EM, Saad-Harfouche FG, et al. HPV vaccination: pilot study assessing characteristics of high and low performing primary care offices. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:157-61. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29868360

- Oliver K, Frawley A, Garland E. HPV vaccination: population approaches for improving rates. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1589-93. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26890685

- Zimet G, Dixon BE, Xiao S, et al. Simple and elaborated clinician reminder prompts for human papillomavirus vaccination: a randomized clinical trial. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S66-S71. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29502640

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. What works: increasing appropriate vaccination: evidence-based interventions for your community. Atlanta (GA): CPSTF; 2017 Nov. Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/What-Works-Factsheet-Vaccination.pdf

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. Increasing appropriate vaccination: standing orders. Atlanta (GA): CPSTF; 2016 Jan 20. Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Vaccination-Standing-Orders.pdf

- Kempe A, O'Leary ST, Shoup JA, et al. Parental choice of recall method for HPV vaccination: a pragmatic trial. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20152857. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26921286

- Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, et al. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine. 2015;33(9):1223-9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25448095

- Fiks AG, Luan X, Mayne SL. Improving HPV vaccination rates using Maintenance-of-Certification requirements. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150675. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26908681

- Rand CM, Schaffer SJ, Dhepyasuwan N, et al. Provider communication, prompts, and feedback to improve HPV vaccination rates in resident clinics. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29540572

- Kempe A, Saville AW, Dickinson LM, et al. Collaborative centralized reminder/recall notification to increase immunization rates among young children: a comparative effectiveness trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(4):365-73. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25706340

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. AFIX (Assessment, Feedback, Incentives, and eXchange) [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [cited 2018 May 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/afix/index.html

- National HPV Vaccination Roundtable. Resource library [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): the Roundtable; [cited 2018 May 31]. Available from: http://hpvroundtable.org/resource-library

- National HPV Vaccination Roundtable. Clinician and health systems action guides [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): the Roundtable; [cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from: http://hpvroundtable.org/action-guides

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS and performance measurement [Internet]. Washington (DC): NCQA; [cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from: http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement.aspx

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. NCQA updates quality measures for HEDIS 2017 [Internet]. Washington (DC): NCQA; 2016 Jul 5 [cited 2018 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.ncqa.org/news/ncqa-updates-quality-measures-for-hedis-2017

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020 topics and objectives: immunization and infectious diseases objectives [Internet]. Washington (DC): DHHS; [updated 2018 Mar 22; cited 2018 Mar 26]. Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives

- National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Strengthening the effectiveness of national, state, and local efforts to improve HPV vaccination coverage in the United States: recommendations of the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Washington (DC): NVAC; 2018 Jun 25. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2018_nvac_hpv-report_final_remediated.pdf