Reflections On the 50th Anniversary of the National Cancer Act

We are not in search of a magic bullet, but rather are attempting to mobilize the best brains available in this nation and the world to ensure that they have an opportunity to make their maximum contribution to the cause of solving the cancer problem and of minimizing the time required for the solutions to benefit the cancer patient."

-Benno C. Schmidt Sr., first chair of the President’s Cancer Panel

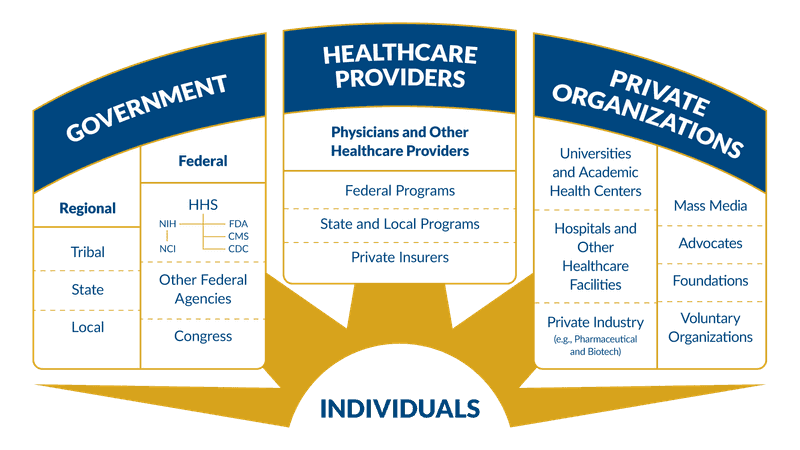

When President Richard Nixon signed the National Cancer Act of 1971, the United States put in motion a coordinated system of federal and nonfederal organizations and partners to address the nation’s cancer burden. The act expanded the authority of the director of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to plan and develop a National Cancer Program that included NCI, other research institutes, and other federal and nonfederal programs. The same act also expanded NCI to its current form and provided funding for fifteen additional cancer research centers, local control programs, and an international cancer research data bank. The act also established the President’s Cancer Panel (PCP).

The PCP is a committee of three members who are appointed by the President to advise on the progress of the National Cancer Program and identify barriers to progress. Despite the close connection the panel has to NCI, the PCP’s work is independent and has a much broader scope. This can be seen in the diverse subjects that the PCP has discussed over the last 50 years. Some examples include:

- In 1974, the PCP expressed concern about the stagnating budgets of the other National Institutes of Health (NIH). While the budget of NCI had substantially increased following the ratification of the National Cancer Act, the same did not happen for the other institutes; in 1974, NCI’s budget was almost five times larger than the budget of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The panel recognized the importance of a strong foundation of research across fields to battle cancer and warned that "neither the cancer program nor biomedical research in general can thrive if these institutes are not healthy.” In the years since, Congress has invested in biomedical research across all of the National Institutes of Health, and the NIH's overall budget in 2020 was $42 billion dollars.

- In 1996, the PCP recommended that participation in clinical research ought to be a part of the standard of care for cancer. This is now reflected in the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, a nonprofit organization that develops cancer treatment guidelines.

- In 2012, the PCP recommended that states increase access to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination services by allowing pharmacists to administer the vaccine. As of 2018, 39 states and the District of Columbia expressly allow pharmacists to administer the HPV vaccine.

- In 2016, the PCP identified a lack of internet access was preventing patients from accessing health information and recommended that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), internet service providers, and nonprofit organizations support programs to increase internet access. Although more work remains to be done, the FCC estimates that as of 2019 the number of Americans living without access to broadband internet has decreased to 14.5 million, a 45% decrease from 2016.

- In 2020, the PCP identified cancer screening as an essential issue that will need additional support and innovation. Early detection of cancer is one of the most important factors in a positive outcome. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a significant decline in cancer screening and it has been projected that this could lead to at least 10,000 excess deaths from breast and colorectal cancers alone. As such, the panel’s 2021 report will be on this important topic.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed existing challenges in our health care systems and caused new ones, especially regarding cancer screening. 2021 marks the somber occasion of COVID-19 becoming the number one cause of death in the United States. However, reflecting on the 50th Anniversary of the National Cancer Act and the successes we have achieved, it reminds us that coordinated work to improve research and access to prevention, screening, and treatment can have transformative results.