Health Disparities in Cancer Part 1: The meaning of "Race" in Science

Throughout its history, the President’s Cancer Panel (PCP) has explored the causes of and possible solutions to disparities in the nation’s health care system. This blog series will explore three PCP reports focused on this important topic.

Mr. President, we conclude that race does not exist from a biological perspective, but that racism, rooted in the social concept of race, does exist."

-Dr. Harold P. Freeman, in a letter to President Clinton in 1997

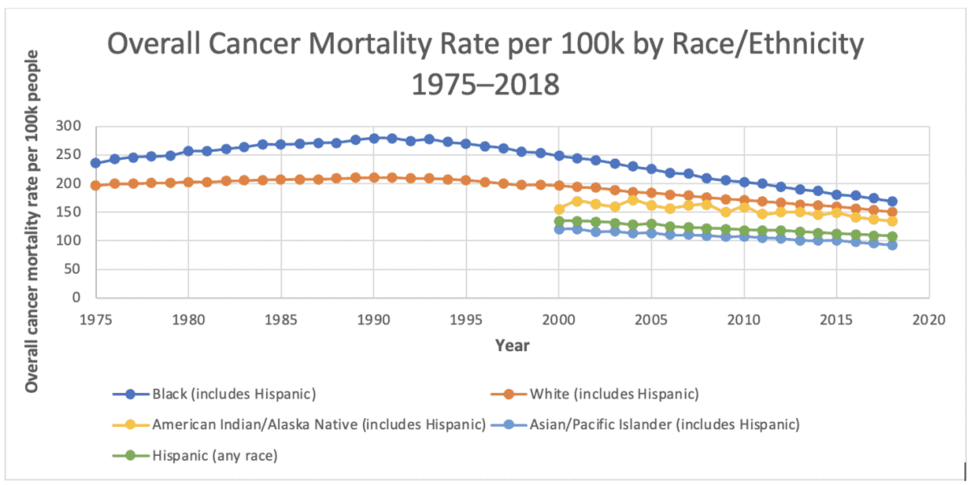

It has been known for some time that the burden of cancer does not affect all populations equally. In 1975, 4 years after the signing of the National Cancer Act, the overall cancer mortality rate for Black Americans was 20% higher than for White Americans. Fifteen years later in 1990, this disparity was even greater, with Black Americans facing a cancer mortality rate that was 33% higher than White Americans.

Historically, differences in medical outcomes such as these were attributed to innate biological differences between people of different races. However, by the mid-1990s advances in genetics had indicated that there is little genetic variation between human populations. In fact, most genetic variants identified to that point could be found among members of the same population.

It is in this context that the President’s Cancer Panel (PCP) convened a meeting in 1997 titled “The Meaning of Race in Science—Considerations for Cancer Research.” This meeting brought together experts who discussed research on the history of racial classifications and their use, how well social definitions of race related to human genetics, the use of racial and ethnic classifications in scientific research, and the scientific and societal implications of race in cancer research.

PCP Chairman Dr. Harold P. Freeman reported the results of the meeting to President Clinton. In his letter, he identified four key findings:

- Race as used in the United States is a social and political construct derived from our nation’s history. It has no basis in science or anthropology.

- Biologically distinct races do not exist. Indeed, there is no evidence that they have ever existed in the recorded history of the human community.

- Neither is there a basis for racial classification. Modern technologies for measuring and conceptualizing human variation reveal that approximately 85% of all variation in gene frequency occurs within populations or races and only 15% occurs between such populations.

- Racism, rooted in the erroneous concept of biological racial superiority, has powerful societal effects and continues to influence science. The cultural framework of societal, institutional, and civilizational values in which science is conducted, and the role science has played in constructing and legitimizing race and racism, must be recognized and addressed.

Significant progress has been made against cancer. As of 2018, the overall cancer mortality for Black Americans saw a 37% reduction compared with 1990. However, even today Black Americans have a 13% higher mortality rate than White Americans. Since 2000, data for other races and ethnicities indicate that American Indians/Alaska Natives, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics all have cancer mortality rates lower than Black and White Americans. Although the 15% of genetic variation that occurs between populations can explain some differences in cancer outcomes, it is not the full story.

Establishing that race is a social rather than a biological construct is important because it shows that disparities in cancer outcomes are not predetermined by race. If race isn’t the sole factor in cancer health disparities, what is? This question will be addressed in the next part of this series, “Voices of a Broken System.”