Health Disparities in Cancer Part 3: Facing Cancer in Indian Country: The Yakama Nation and Pacific Northwest Tribes

Throughout its history, the President’s Cancer Panel (PCP) has explored the causes of and possible solutions to disparities in the nation’s health care system. This blog series will explore three PCP reports focused on this important topic.

"Indian communities have inadequate resources to conduct cancer education, encourage cancer screening and prevention, and help patients obtain cancer-related care, either within the IHS [Indian Health Service] system or in the non-Indian community... Facing cancer in Indian Country should not be more arduous than it is elsewhere in our nation"

-President's Cancer Panel, letter to the President

"We need to have someone not only get the data... but do something with that data. Something that is productive. Something that causes services to become available to us. Something that causes the Indian Health Service to have more care providers for us."

-Anita Pimm Swan, breast cancer survivor and wife of bladder cancer survivor, Yakama Nation, Washington

In 2000 and 2001, the President’s Cancer Panel (PCP) held a series of regional meetings to explore the barriers that prevent Americans from receiving cancer care. The testimony gathered at these meetings led to the 2001 report Voices of a Broken System. During one of these meetings, Mr. Joe Jay Pinkham, a Yakama tribal elder and cancer survivor, invited the PCP to visit the Yakama Nation to learn firsthand of the challenges faced by the Yakama and other Pacific Northwest tribes. Dr. Harold P. Freeman, the chair of the PCP, visited the Yakama Nation Reservation over 2 days in 2002. The meeting was attended by tribal elders and members of the Yakama Nation and other tribes in Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. There was also testimony from health care and social service providers, officials of the Indian Health Service (IHS), community epidemiologists and researchers, advocates, and state legislative staff. The final report, Facing Cancer in Indian Country: The Yakama Nation and Pacific Northwest Tribes was the result of this testimony. In this report, the PCP made several recommendations to improve Native American health. Three are highlighted below:

Recommendation 1: Funding for Indian health care through the Indian Health Service (IHS) must be increased.

"We only have four physicians taking appointments. That leaves approximately 5,000 plus patients per doctor. When you talk about cancer prevention how can one prevent cancer when you cannot even keep up with the onslaught of patients coming through the door? When you cannot get an appointment for two months?"

— Rex Quaempts, M.D., family physician, Indian Health Service; member, Yakama Nation, Washington

"It took me six months to get a referral out because I am not a Quinault but I lived in their service area, [and] my Quileute tribal service area could not give me the referral because I was out of jurisdiction of their service unit. Things like that need to be looked into and addressed because a lot of times we cannot marry someone from our own reservation because we are all related in one way or another so you have to go look outside of your reservation to go marry someone you are not related to.”

— Ann Penn-Charles, breast cancer survivor; community health representative, Hoh Indian Tribe, Washington

"...They had drained out five liters of liquid from her stomach. They found a tumor that was the size of a grapefruit and four more that were the size of walnuts... and all of this, you know, I think could have been prevented if they would have listened to what she said about her stomach hurting... I am thankful that the IHS is there, but, you know, when a person hurts in their body a lot of times they think they are there for drugs"

— Tina Kalama Aguilar, warm Springs Tribe, Oregon, describing the experience of a friend with ovarian cancer

The IHS is an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services that provides health services to American Indians and Alaska Natives. Many members of the Yakama Nation live in rural regions and rely on facilities operated by the IHS. Unlike Medicare and Medicaid, the IHS is not an entitlement program, and its budget must be appropriated by Congress each year.

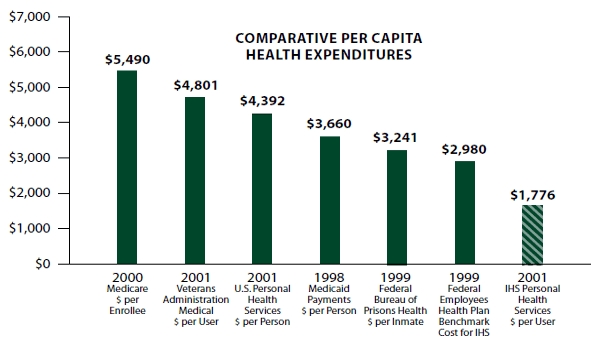

The PCP found that the IHS did not have sufficient funding to fulfill its mandate and that there was a significant shortage of staff and resources at IHS facilities. In 2001, the IHS spent $1,776 per user of its services. By comparison, the Veterans Health Administration spent $4,801 per user that same year, and in 1999 the Federal Bureau of Prisons spent $3,241 per inmate on health care.

The situation has improved since 2003. The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) had a positive impact on the IHS in several ways. The ACA included the permanent reauthorization of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, which contains several provisions to empower the IHS to support Native American health. The increase in Americans with insurance coverage since the passage of the ACA has also benefited the IHS. In addition to funding through congressional appropriations, IHS is able to bill patients’ insurance, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance. Between 2013 and 2018 the proportion of patients at IHS facilities with insurance grew from 64% to 78%. This has increased revenue through billing by over 50%, allowing IHS facilities to expand services and hire more staff.

There have also been amendments to cancer screening and treatment programs to ensure that Native Americans and tribal organizations can take advantage of them. For example, the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program provides funds for cancer screening in underserved populations. American Indian and Alaska Native tribal organizations have been eligible for this program since 1993. In 2001, Native Americans screened through this program became eligible for treatment through Medicaid.

Between these reforms and increased congressional appropriations, the Government Accountability Office found that in 2017 IHS spending had increased to $4,078 per patient. However, this is still short of what is seen in similar agencies. That same year, for example, the Veterans Health Administration spent $10,692 per patient.

Recommendation 2: Increased efforts should be undertaken to develop more accurate data on the cancer burden experienced by native Americans in the Pacific Northwest

"The only statistic I was given to bring here is out of the last 40 deaths in Warm Springs, 15 of them [37.5%] were due to cancer... we are catching them too late... our people need to understand that. The way to help them to understand that is to increase awareness..."

— Geneva Charley, community health information specialist, Warm Springs Tribe, Oregon

National data at the time of the PCP report suggested that cancer incidence was lower in American Indians and Alaska Natives than the national average, while cancer mortality was higher. However, the PCP believed that the actual number of cases and mortalities were likely higher than the data indicated. One substantial challenge was that many medical records misclassified American Indians as another race.

Since then, there have been several efforts to improve the quality of data on cancer incidence and mortality in Native Americans, especially in the Pacific Northwest. For example, one team has corrected the race in death certificates by linking them with medical records. Efforts such as these have allowed registries to have much more accurate information about cancer in Native Americans, including differences between geographic regions.

Recommendation 3: Additional research is needed to better understand the possible relationships between environmental exposures and cancer in Pacific Northwest Native Americans

"Plutonium is one of the most hazardous materials in existence. One invisible speck inhaled into the lungs can cause cancer. Hanford produced 74 tons of plutonium."

— Russell Jim, manager, Environemental Restoration/Waste Management Program; elder, Yakama Nation, Washington

"One of the scientist we met with the other day... was from EPA [Environmental Protection Agency]. She said, if you eat 100 pounds of fish a year out of the Columbia River, we could not guarantee how long you would live."

— Bob Brisbois, Business Council, Spokane Tribe, Washington

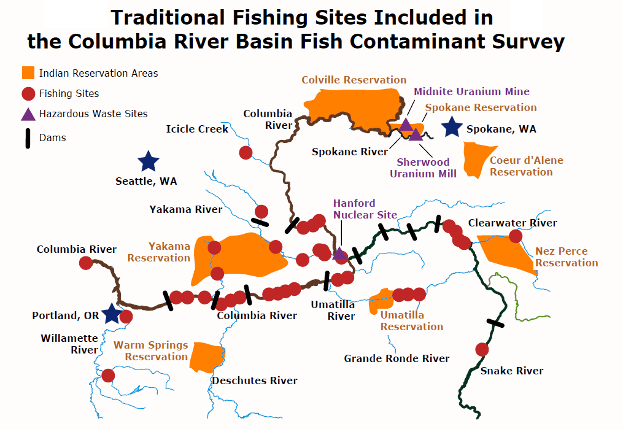

Fish in the Columbia River basin have been a major source of food for the Yakama and other nearby tribes for generations. However, the river has been contaminated with chemical and radioactive pollutants. One of the most significant sources of this was the Hanford Nuclear Site, which was once used to generate plutonium. Pollutants from this and other sources have been detected in the fish in the river, meaning that the people who rely on the river for food and eat those fish are also being exposed to the same toxins.

Unfortunately, similar problems exist for tribes in other parts of the country. Between 1944 and 1986, nearly 30 million tons of uranium ore were extracted from Navajo lands in the Southwest United States under leases with the Navajo Nation, and several watersheds were polluted. The Sequoyah Fuels Corporation uranium processing plant in Oklahoma, now decommissioned, caused soil and groundwater contamination in Cherokee land.

Since 2003 there have been several projects to remediate pollution in Native American land. The Columbia River Restoration Program, established when Congress amended the Clean Water Act in 2016, is a grants program that supports environmental protection and restoration projects throughout the Columbia River basin. The EPA is supporting cleanup efforts at abandoned uranium mines on Navajo land. Finally, radioactive waste from the Sequoyah Fuels Corporation has been removed.

Despite this progress, significant challenges remain. Climate change has had severe consequences for salmon populations in the Pacific Northwest. The loss of this traditional food source is a major threat to the way of life of Pacific Northwest tribes.

Conclusions

Nearly two decades have passed since the PCP published The Meaning of Race in Science, Voices of a Broken System, and Facing Cancer in Indian Country. In this time, significant progress has been made to reduce cancer disparities. Yet, work more remains to ensure that the burden of cancer is reduced for all, and the PCP will continue to shine a spotlight on these important issues.